The grief and gifts of abolitionist struggle

The many lives we lost this year - in the form of executions, worker deaths and more - has both deepened my intimacy with despair, and strengthened my resolve to fight on.

I’ve been procrastinating on writing and updating this blog for the last few months, which have been a whirlwind of events, conferences, campaigns and other organising efforts. While I haven’t written as much this year as I wanted to, there are a few pieces I thought I’d share as the year wraps up.

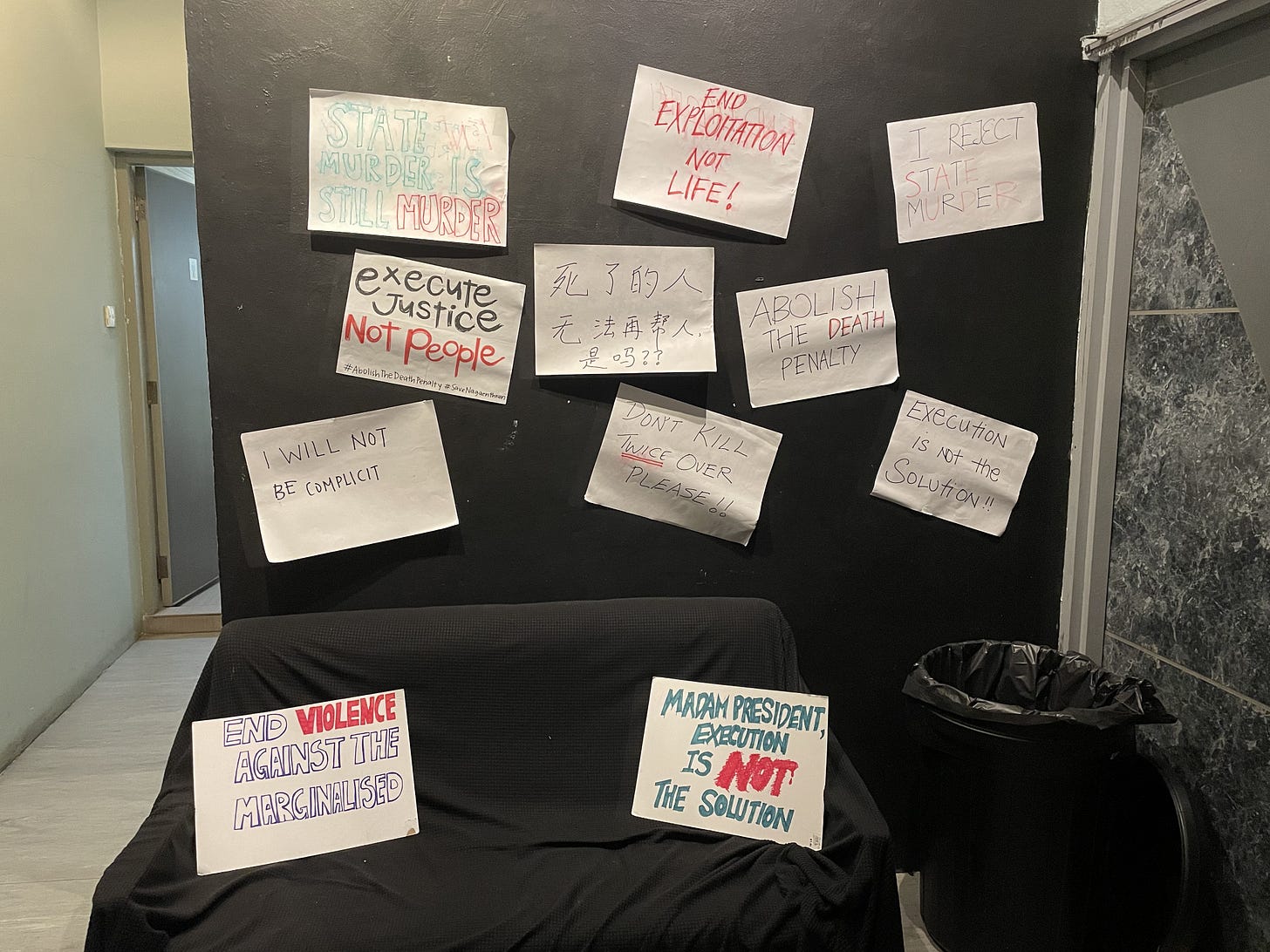

In Oct/Nov 2022, we at the Transformative Justice Collective organised a series of events - called Free Them, Free Us - in commemoration of World Day Against the Death Penalty. The opening event, ‘End Oppression, Not Life’, featured four mini-lectures on the struggle for abolition. Here is the transcript of my speech at the event.

On many nights this past year, I’ve woken from nightmares where I am trying to break someone out of death row. Sometimes, we’re running for hours, prison guards at our heel. Sometimes, I take the place of the prisoner, and they escape. Sometimes, I fail, and watch, kicking and screaming, as the prisoner is taken to the gallows.

I don’t begrudge my subconscious these dreams. The world I wake up to is far more terrifying.

It is a world in which there are many death penalties, each one a fresh horror. When workers forced to travel in the back of lorries die on the road, it is a death penalty. When bodies are scorched in factory fires, or crash into the ground from skyscrapers they are cleaning, it is a death penalty. When the poor lose limbs and then their lives because they can’t afford timely healthcare, it is a death penalty. When an overworked bus driver keels over his steering wheel after bringing his bus safely to bay, it is a death penalty. When a domestic worker is starved and her breath is beaten out of her body, it is a death penalty. When 12-year-old children jump off buildings because they believe that their life is worth nothing more than exam marks, it is a death penalty.

My favourite Tamil poet, Bharathiyar, writes, “தனி ஒரு மனிதனுக்கு உணவில்லை எனில் இந்த ஜகத்தினை அழித்திடுவோம்”.

“If even a single soul must go without food, then let us destroy this world.” It sounds dramatic; us Tamils tend to be that way. But since I was a child, I have always found it deeply moving because it is a declaration that resists disposability. Not even one among us can be sacrificed. One unjust death is too many. Because once we learn to tolerate the disposal of fellow human beings, we snuff out a part of us that is vital to keep burning if we are to win back this earth for the people.

Said Zahari, a Singaporean writer who led a journalists’ strike for press freedom, was detained by the PAP government under Operation Coldstore, a few months before the birth of his daughter. Upon her birth, in May 1963, he writes from prison,

“I am the father,

robbed of my freedom,

whose world has shrunk

into a dark little dungeon.

My child, just born

into a world yet unfree.”

Here, Said Zahari reflects on how, though it is him that lives in a prison cell, his daughter, on the outside, is also unfree. All of us who live in this society full of cages, coercion and fear, are unfree. As long as the bodies and dreams of our fellow people are caged - whether in Changi prison or in worker dormitories, whether in psychiatric wards or juvenile homes – we are all unfree.

Lee Siew Choh, who left the PAP in 1961 and became a leader of the Barisan Sosialis, said “Half the strength of the PAP has come from the fear it has instilled in the minds of the people.” Our history is checkered with mass detentions without trial conducted under PAP rule, the incarceration of workers, unionists, students and political leaders who believed in true Merdeka, who believed in the people. Remember, we have a long history of courageous working-class heroes. The people of Singapore have never been meek. But decades of detentions and white terror destroyed a thriving labour movement and the people’s dreams of democratic socialism. Merdeka never came.

In Singapore today, increasingly sophisticated systems of control, reward and punishment keep us unfree. CCTV cameras watch us wherever we go. They monitor prisoners in their cells, domestic workers in their homes, and all of us as we walk down the streets or take public transport. Workers are arrested and deported for daring to protest unjust working conditions. Tragically, our families, schools, media, places of worship, and welfare systems are often deployed to indoctrinate, discipline and punish us. I think one of the greatest cruelties of our oppressors is how they constantly use us to betray each other. We are taught to coerce and police each other, rather than love and nurture each other. We are taught to fear each other, not to see each other.

The hangman, the prison guards, the police officers, the doctors who certify death, the spiritual counsellors who coax the prisoner to walk obediently to the gallows, they are all workers used directly by the state for the smooth administration of murder. But we are all made complicit in this theatre of punishment. The state constructs and sells us enemy images – of dangerous criminal masterminds, the fearsome Other that we need to be protected from, by no other than the government itself. They convince us to give them the power to kill, torture and cage our fellow people by promising us that it’s for our safety. In this way, they maintain a narrative that we are always on the brink of disaster, saved only by their violent use of power.

The way in which the death penalty is carried out in Singapore is emblematic of PAP’s distinct strongman brand. Even though we don’t have public executions, they are still a powerful spectacle, in their hiddenness - the final act in the political theatre that begins with news reports of epic CNB raids, courtroom reporting, and the sentence of death passed, followed by silence. After they are sentenced to death, they disappear. The message? We are taking care of the dirty business for you.

Throughout history, from guillotines to torture chambers – tyrants have used shock punishments – murder, torture – to bolster their power. Punishment is always an expression of power. Whether it is of drug trade workers or political dissenters, the PAP punishes to remind us of its power, keep us compliant and divided.

What our oppressors – the political and business elite – most fear is our rebellion, and that is why, rebel we must. They want us divided across lines of race, gender, nationality and more. Unflinching solidarity is our rebellion. They want us to fear and blame each other. Radical love is our rebellion. They want us to accept our disposability. A deep commitment to each other’s life and freedom is our rebellion.

Being an abolitionist organiser has taught me, as Paulo Freire says, that the greatest love is our commitment to another’s freedom.

Datchina’s mother often says to me, you must have been my daughter in another birth. But am I not, mother, yours, in this one too? I ask her, and she laughs. When we fight alongside each other for justice and freedom, arms linked, we share a bond deeper than family. It is the bond of comrades. I believe our freedom comes within reach when more and more of us link arms in a sisterhood that transcends the ties of blood, race or creed.

Another crucial lesson I’ve learned is that fighting for the lives of our brothers and sisters on death row requires a discipline I have never needed to have before.

The discipline to not look away from unspeakable pain and cruelty, the discipline to stay the course, the discipline to find a way when every door is slammed in your face, and most vitally, the discipline of hope. In this work, I have had many moments of overwhelming despair, during which these words by Cornell West have kept me company:

“Those who have never despaired have neither lived nor loved. Hope is inseparable from despair. Those of us who truly hope make despair a constant companion whom we out-wrestle every day owing to our commitment to justice, love, and hope.”

The death penalty regime in Singapore can feel particularly impossible to defeat because of our undemocratic and opaque systems that operate with impunity, because of aggressive state intimidation, because resources and infrastructures that support activism are extremely scarce, and because our laws render most ordinary tactics of organising and mobilising illegal.

And so it can often feel like we are putting one foot in front of another in pitch darkness. In many such moments, I have drawn strength from the extraordinary spirit and courage of the death row prisoners I’ve come to know. They live behind bars, awaiting a death sentence, and yet, they fight on. Then how dare we not? There is no obstacle we may face, no constraints on our freedom, more daunting than theirs. So many of them tell their families to continue the struggle for abolition even after they are executed. When they are so determined, we bloody well better be. As long as we fight like hell, we have not lost. As long as there is struggle, there is hope.

And struggle, we will, because it keeps us human.

I’d like to end with a few more words by Said Zahari. This time, words he wrote to his wife Sal in 1969, after 6 years behind bars.

“But in spirit we are one,

as always,

bound by unbreakable bonds of love and longing for justice.

Neither this prison wall nor a hundred years of incarceration

shall diminish my love.”

Though Said Zahari wrote this for his wife, I feel it is a fitting ode to the possibilities of love and solidarity that connect all of us on both sides of prison walls, Hong Lim Park barricades, borders, or any other barrier erected by those in power.

We fight on!