Reading against the machine

The following is an essay I wrote for Ridiculous, Untold Tales of Singapore, a collection of essays that was published earlier this year by Function 8, documenting the particular ways in which Singapore’s police state operates and persecutes dissent. The editors invited me to reflect on my experience participating in - and then being investigated for - a protest on an MRT train in 2017, commemorating the 30th anniversary of Operation Spectrum. Since finishing this piece, I’ve continued to think and write about protest and civil disobedience under Singapore’s authoritarian rule. I am working on a follow-up piece that I will be sharing here soon, so do look out for that :)

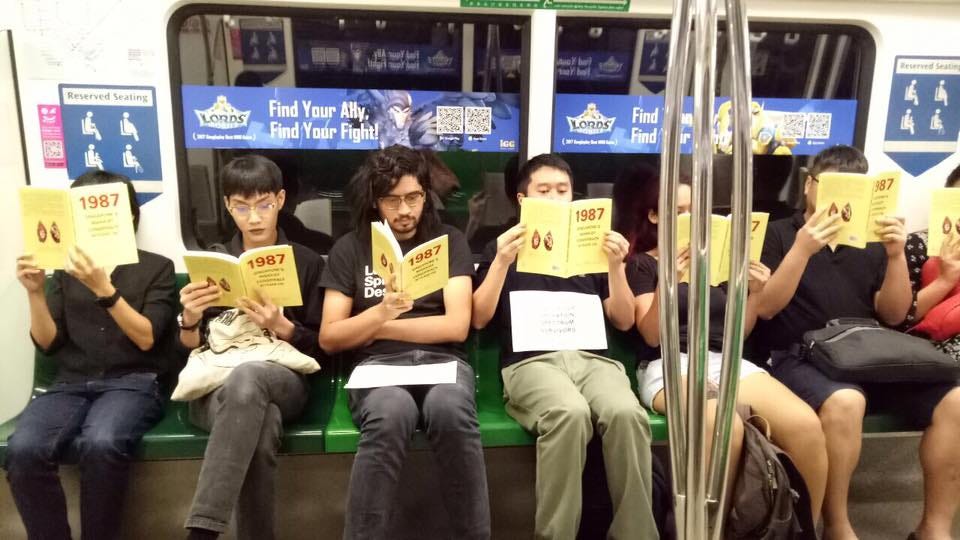

On 3 June, 2017, nine people gathered at the platform of Marina South Pier MRT Station to take part in an action to commemorate the 30-year anniversary of Operation Spectrum. Operation Spectrum is the code name of a “security operation” by the PAP government where 22 individuals were detained without trial and slandered by the PAP government, which accused them of participating in a Marxist conspiracy to overthrow the regime through violent means.

I was one of the nine people who arrived at Marina South Pier that afternoon. Some of us thought we were there for a silent book reading. Others thought of the action as performance art. Yet others understood it to be a protest. All of these are reasonable descriptors of the action, but the fact that it held different meanings for each of the nine of us is an important part of this story.

At the time of writing this, in September 2021, this action remains one of Singapore’s largest and longest (in terms of duration) public assemblies without a permit that has taken place outside of Hong Lim Park in recent years. But that Sunday afternoon, when we gathered at the MRT platform, most of us didn’t have a full picture of how the rest of the day would unfold, let alone the state and societal backlash we would face in the weeks, months and years after.

Four years later, when Jolovan Wham was sentenced for organising the assembly, the public prosecutors called our actions “unlawful antics”. They said there was “detailed, meticulous planning” and “thorough preparedness”. That this was “no spontaneous assembly driven by a spurt of emotions”.

They claimed our actions could have caused “massive disruptions”, accusing us of “dramatically publicising” our cause, and the fact that photos of the action were posted online later made clear our “intent to stir up publicity” and draw attention to ourselves. The train, they said, is a vital part of our transport network that is not meant to cater to civil disobedience, and that we disturbed the peace that commuters should be able to expect while commuting. That there was no way for us to ensure that others would behave civilly even if we did. They even accused us of putting commuters at risk of violence, and illegitimately occupying seats, depriving “real” commuters of seats (the ‘taking up seats’ issue was actually a factor that the judge considered relevant in sentencing!)

Sitting in the gallery, listening to them, I oscillated between amusement, indignation and anger at their characterisations. The prosecutors painted a picture of antisocial elements that selfishly put fellow passengers at risk for a publicity stunt. They told a story about a group of people who choreographed a scheme to cause the maximum disturbance possible to the maximum number of people.

My story is quite different. For one, we were embarrassingly disorganised. For most of us, it was our first time participating in an action like this. Everything came together haphazardly, in bits and pieces. The idea was first raised about a week earlier, during the launch event for the book ‘1987: Singapore's Marxist Conspiracy 30 Years on’, where both Jolovan and I gave speeches.

From there on, it was a bit like a broken telephone, with each of us having different pieces of information, and different ideas for how to make this experience meaningful and poetic. Some of us wanted to express why we cared deeply about justice for Operation Spectrum survivors and the abolition of the Internal Security Act, which allows the state to detain anyone they claim is a threat to national security, without trial or evidence. Some of us wanted to celebrate the book, written by the survivors of Operation Spectrum, and the powerful truth-telling it does, which could awaken more Singaporeans to parts of our history that the PAP government is intent on erasing. Personally, I was moved by the possibility of sharing this book and connecting with other ordinary people, people like us, who might never otherwise encounter these stories, in the most ordinary of spaces we share every day – the MRT.

Among the nine of us, only some knew each other. The rest, we met on the train platform. We didn’t know how many others would be there till we arrived. Some people were surprised to see the blindfolds and signs. We quickly discussed what to do, and decisions were made hastily and clumsily. In many ways, we were naïve, and didn’t believe we would face investigations or charges for this action, as some other actions of a similar nature had slipped under the radar. All we prepared for was that if any MRT security officers or police officers asked us to disperse, we would.

While most aspects of the action and what would happen to us after were not discussed at length, we spent a lot of time working out how to care for other passengers who might be surprised to see this group of us, which is where my role came in. Seven of us would be blindfolded – everyone except Jason Soo and I. Jason, a filmmaker, was there to document the action on film, while I was to engage passengers who were curious, answer any questions they might have, reassure anyone who might be confused or perturbed, and take some photos. For those who were interested, I was to give them bookmarks with more information about the book and where to find it. Since the others involved in the action would be blindfolded, I was also to be their eyes. If there was any sign of commuters getting agitated or anxious, I was to alert the others immediately and we would stop the action. We even joked that I was to be the “care and safety officer” for this event.

These are flashes of memory, my strongest impressions from the next few hours: We let a crowded train pass, waiting for one where our presence wouldn’t be too jarring. Between trains, we laughed about how anticlimactic it was that a cabin we boarded had no other passengers for the whole stretch. We slapped our foreheads when we realised that of course, no one’s going to be in the Central Business District (CBD) on a Sunday afternoon!

At first, some people blindfolded themselves while others decided to read the book. One of us actually managed to read two chapters of the book while we were riding the trains. “How can we read if we’re blindfolded?” someone complained. “But it’s poignant! The state controls what we see, hear and read!” someone else replied. Later on, all seven people holding the book agreed to be blindfolded for a more “consistent aesthetic”. Some passengers thought we were shooting a film, which tickled us.

We had gotten off the train, when suddenly we realised that the signs we had stuck to the windows with blu tack – signs calling for the abolition of the ISA and justice for Operation Spectrum survivors – were still up! Two people in our group dashed back into the train at the last minute to take them down, and took the train back in the opposite direction to meet us. “Such noobs we are!” we giggled, as we ate dinner together before we headed home. “Surely, if anyone watching the MRT CCTV sees us, they’ll realise we’re a bunch of harmless amateurs,” we joked. The whole experience was nerve-racking, uplifting, comical.

To borrow a phrase from a friend, we “stumbled through” that action. And stumbling through can be a wonderful way to learn, to discover, to play, to surprise ourselves. Especially in Singapore, where the growing repression of civil and political liberties means there are not many reference points in recent history of direct action, stumbling through is a core feature of political praxis.

We made many mistakes, but not the kind the state accused us of. Our mistakes were not learning each other’s boundaries well, not taking enough care to ensure that all of us were comfortable with every decision, not preparing for what was to come, not adequately protecting each other from the repercussions that followed. These mistakes were grave, and they had heavy consequences.

For some, it strained our friendships with each other. Some of us lost our jobs, and had trouble finding work for years after. Some of us had threatening letters sent to our employers and homes. Some of us were overwhelmed by the scathing media attention, the contempt in the public response, the distress of family members, the censure of some peers in civil society. We all faced police investigations, hours of interrogation. Some of us had our phones seized. Jolovan received a fine, and served a prison sentence in lieu of it. The rest of us received a ‘stern warning’ from the police. In the face of all the backlash, we tried to take care of each other, but we didn’t always succeed.

As anyone might expect, I learnt many important lessons from this experience. I think we all did. It tested my principles, my relationships, my limits. It also revealed a lot about civil society, progressive thought and public discourse in Singapore at the time, laying bare where we stood with each other. The most important lesson I learned was that every act of repression by the state is designed to rip us from each other, and if we are to stand a chance against the relentless suppression of dissent in Singapore, we need to practise radical care and tenderness with each other. We need to build deep and enduring trust, we need to honour and respect our peers, we need to build a real and formidable solidarity. A few years later, when I organised a public protest against MOE’s transphobic practices, I knew that care, continuous consent and a deep connection to each other and to our shared conviction in the action had to be centered.

I am clear on this: the state makes dissent incredibly costly to ordinary people. But we have to flip the script. We have to, instead, make repression costly to the state, and we can only do that through building resilient, responsive communities and movements.

There is much I regret about how we did this action, but I do not regret the action. I am proud to have been part of it. Bearing witness (in my case, as the one who was not blindfolded, quite literally) to this action showed me the visceral, embodied magic of a public assembly. It taught me why the freedom of assembly is a sacred one, and why the state is so afraid of us awakening to its power.

It was incredible to see my peers shoulder to shoulder, holding up this precious book – silent, yet communicating so much. To watch them blindfold themselves, making themselves even more vulnerable. Standing resolute, for hours, not because they were unafraid, but despite being afraid.

It was transformative to see passengers respond to this image of conviction, of courage, of freedom. They were curious, surprised, some were visibly moved, and some were concerned for my friends. “Isn’t this illegal?” a few asked me. “It could be seen to be. But do you think they’re a threat? That what they’re doing is harmful?” I asked. None of the people who spoke to me thought so. Perhaps it is my projection, but many times, I thought I saw something pass between our eyes. A shared reckoning. A recognition, not of something familiar, but that perhaps this experience – of our fellow people putting their bodies on the line, standing up for what they believe in – shouldn’t be so unfamiliar.

Many people are skeptical of the value of freedom of assembly. Why can’t you go to Hong Lim Park? Why can’t you just make your point on social media? Why don’t you submit a forum letter? Put up an online petition? Have you tried writing to your MP? Or closed door meetings with a Minister? These are common refrains that protestors face.

To me, the right to gather represents our right to meet our fellow people in our common spaces, to articulate our shared struggles and confront our oppressors. It is an unpolluted, natural and spontaneous expression of democratic instinct to come together, to sit (or stand, or dance) with each other, and with discomfort.

Some people defend protests by declaring that they are not disruptive. I believe they should be disruptive. Disruptions are a gift. They are life-giving. They break us out of cycles and dynamics that don’t serve us anymore. Protests should disrupt oppression, exploitation, abuse. They are a community alarm system, to alert each other when something is wrong, to stop us in our tracks, to interrupt our slumber, to jolt us out of inaction. They are a reminder to reject obedience to our oppressors, a reminder that we can take up space, that we can make demands, that it is we ordinary people who keep the world going round, not our masters, and that this is not a game of cards — this is your life, and mine.

Limiting our freedom of expression to Hong Lim Park robs us of the power to encounter each other where we are, and it robs us of context where it matters. A protest is an intervention into everyday life, it is not necessarily an event with a date, time, respectable venue and a roster of speakers. A protest meets you on the streets, on the train, in your neighbourhood, at your workplace, outside your church. If I am protesting the suffering of transgender students in public schools, the context is the Ministry of Education’s policies. If I hold a sign outside MOE telling them to stop hurting our children, the action preserves this context. If I hold the same sign at Hong Lim Park, those in power never have to confront my challenge, my demands, my refusal of their atrocities.

If we organize a protest at Hong Lim Park, those who care about the issue can show up and hear what I have to say. If we protest on the streets, people who pass by have to contend with the politics and poetics of our action on their way to work, home or a date. And perhaps it will shift something in them. Protest is one of the most accessible forms of political participation and expression available to ordinary people who don’t have a voice in parliaments, at podiums or in the press.

The prosecutors who brought the charges against Jolovan claimed that the use of public facilities or public spaces for a public assembly was an “aggravating factor” because society should be able to “go about its affairs” without any disturbance. They spun yarns about how, in a congested city with millions of people, the risks of violence breaking out as a result of a public assembly are especially acute, and cannot be tolerated in any fashion. What they are saying, what the Public Order Act says, is that our public spaces are not ours at all. That we cannot trust ourselves with each other.

I believe that a public assembly is a love letter, a trust fall, a celebration, a reclamation. I refuse to let a ridiculous law, police intimidation and prosecutorial gaslighting tell me otherwise.

The trains belong to us, the people. We build them. We swing from their handles, stare out their windows, play five stones on their floors, get lost in a book and miss our stop. The trains belong to us. And we? We belong to each other too. This belonging can be felt in many places, not least at a march, a sit-in or a silent book reading where the bodies next to us hold us up, reminding us that we’re in this together.