"If I could give my life in exchange for his, I would": Yet another sister fights for her brother's life

The Singapore state plans to take Tangaraju Suppiah's life next week. His sister, like so many other sisters of death row prisoners, is determined to save his life.

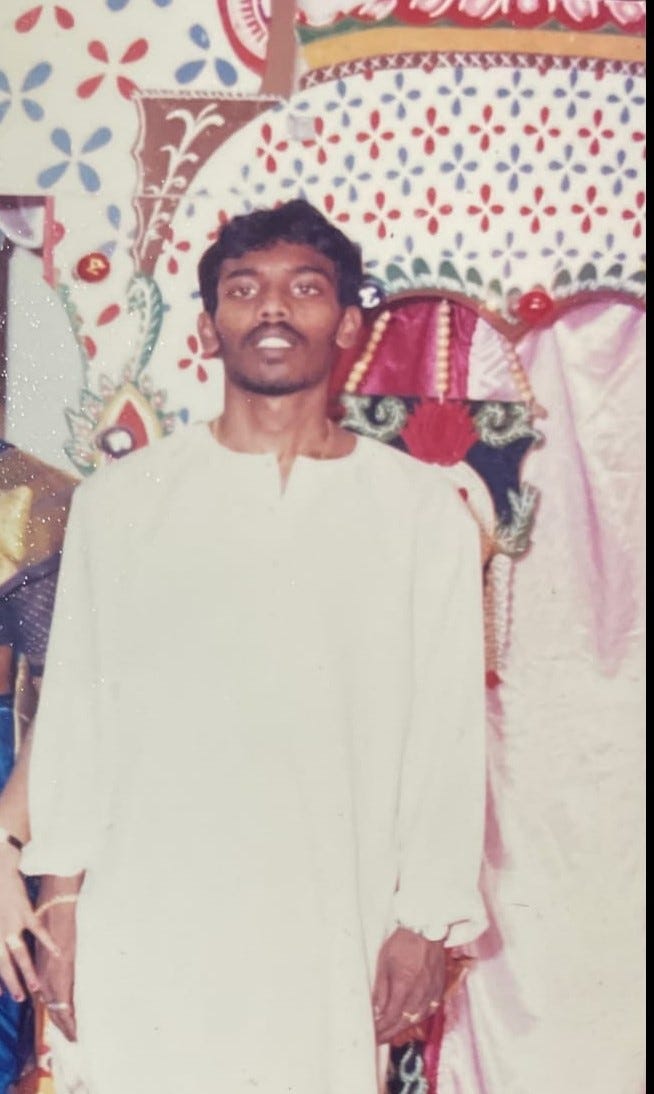

Tangaraju Suppiah, a 46 year-old Singapore Tamil man, is scheduled for execution on 26 April 2023. If it goes ahead, this will be the first execution in Singapore this year. In 2022, Singapore executed 11 men, all for drug-related charges. Tangaraju was convicted of abetting an attempt to traffic cannabis that he had never seen nor touched, and sentenced to the mandatory death penalty. His story is the story of a child who never had a chance.

When Tangaraju Suppiah, or Appu, as he was lovingly named by his paati (maternal grandmother), was a child, he loved eating laddus (an Indian sweet) and prawn curry. His sister Leela, who is 3 years older, describes him as a mischievous but gentle boy. The two were inseparable.

“We never fought, the way other siblings do,” she tells me in Tamil. “We grew up in a humble one-room rental flat. My mother was a single parent, a cleaner employed by the government. And my grandmother was a gardener for Jurong Town Corporation. The two of them raised us.”

The left-behind children

Appu attended Merlimau primary school, but struggled with his schoolwork, and dropped out in Primary 5. When he was 12, Appu was introduced to weed by older friends in his Taman Jurong neighbourhood, and like a curious, innocent child might, he tried it. Soon, it became a habit.

When Appu was first incarcerated, he was only a 14-year-old child. He spent the next few years in a Boys’ Home – a juvenile facility for children whom the state decides are “problems” – for having taking some weed. He was then transferred to an adult prison facility when he was 16, after he was found using weed again during home leave from the Boys’ Home. Appu has spent most of the rest of his life in prison, with increasingly long sentences - always for cannabis consumption and possession.

Talking to his family, I realised with a sinking heart - Appu’s story is that he never got to have one. He never got to live a life. When I ask Leela if she would like to share her favourite memories of him, or what his interests were, she looks at me helplessly. “I don’t know what to say…he’s never been with us, he’s always been inside. He never got to develop hobbies or interests.”

Her dominant memories of him are prison visits, which she has made weekly for more than 27 years. I met Leela outside Changi prison on Thursday, after her visit with Appu. A staff member from the Prison Link Centre (the department that coordinates visits) stops to talk to Leela on her way out. She squeezes Leela’s shoulder and says some soothing words to her quietly. After she leaves, I ask Leela what she said.

“We’ve known each other for 27 years,” Leela smiles. “She told me she’s very sorry to hear the news, and asked me to stay strong. She’s praying for my brother too. They all know, my brother is a good man. You know, there is no one in the world who will say they don’t like Appu? No one has a bad word to say about him, everyone likes him,” she beams proudly.

It is chilling how familiar Appu’s story is. Nazeri bin Lajim (executed in October 2022) developed a dependence on drugs when he was 14 and was first sent to prison at just 16 years of age. Syed Suhail (who remains on death row after he was granted a stay of execution in September 2020) was about 14 years old when he started using drugs. He was sent to the Reformative Training Centre (prison for kids) soon after. Abdul Kahar (executed in March 2022) was 18 when he was first sent to prison for drug use. He had started using drugs a few years prior.

All these children went on to spend the majority of their lives in and out of prison, relapsing soon after they were released each time. They were all ultimately convicted of acts related to drug trafficking and sentenced to the mandatory death penalty. Who can look at these stories with an honest heart and see the “holistic, harm prevention approach” the PAP government and Central Narcotics Bureau shamelessly boast about?

The government and mainstream media want you to believe the story that the people on death row in Changi are dangerous, conniving drug traffickers. But that’s not the truth, not by a long shot. Appu, Nazeri, Kahar, Syed – their stories are stories of how our systems and society have betrayed children. These were all children who developed a dependence on drugs, and were discarded, left to rot behind bars for struggling, for not being able to beat an addiction on their own. They didn’t receive therapy, care, understanding or any form of support.

I am reminded of death row prisoner, poet, feminist and philosopher Pannir Selvam’s words, when he wrote in a letter from Changi Prison, “Before they take your life, they will try to take everything else they can from you – your freedom, dignity, rights, dreams, hope, value, and respect. Everything, like a vacuum cleaner, sucked away before our lives are ended.”

While other children were in school, going to art classes, spending time with their families, squabbling with siblings, playing football and video games, enjoying music, making friends, going to movies, discovering their passions, developing crushes, these children were locked up. Instead of the love and affection of their families and communities, these children were “raised” under the punishing watch of corrections officers and prison guards. They were treated only with cruelty, harsh punishments and stigma. They never had a chance. The PAP propaganda machine loves to go on about how they make sure “no child is left behind”. Well, here they are, the left-behind children.

“His entire socialisation happened in prison,” Appu’s uncle explains to me. “He was sent to prison at such a young age, and surrounded by people older than him. He only knew life in prison, he didn’t know how to live outside of it. Even when he comes out, who does he know, except the guys he was in prison with…for 5 years, 8 years at a time? That was his whole world.”

Talking to their families, it quickly becomes very clear that each time their loved ones were released from prison, there were no services or resources offered to support them with transitioning to life outside. They struggled to build a life, eventually leading to a relapse.

All of us, when life gets to be too much, turn to the things that give us an escape – whether it is binge-watching TV, scrolling social media, drinking, smoking, shopping, or anything else. Most of us cannot imagine the pain, alienation, discrimination and helplessness that ex-prisoners face while trying to adapt to the demands of school, work and life after long years of incarceration. These young people tried to cope in the ways they knew and had access to – using drugs.

But they didn’t harm anyone. Not one of them was violent towards their family members or strangers as a result of their drug use. They were never a threat - they were just trying to get by in the only ways they knew how. In my view, none of them should have ever been behind bars, let alone hanged to death.

Glimpses of Appu’s spirit

Appu’s cousin, uncle and friends, all struggled to recollect stories about him in my conversations with them. But even in the little time they’ve had with him, between long periods of incarceration, they all agreed – he was always kind, generous and helpful to everyone who met him.

“If a friend was in trouble, he was the first one there,” a cousin tells me.

“He had very little, but he would give away what he had if someone asked,” Leela says.

“Even when he was on the street, with no place to live, he would ask me how he could help me with my own problems. Even when he’s in prison, on death row, he’s always cheerful, always asking about the family. He must be so afraid, and he must be suffering so much, trapped within four walls all these years, but he’s never once revealed his pain to us. He also doesn’t ask for anything, during my prison visits. He will sometimes ask me to get CDs for other prisoners, because there are songs they want to listen to. But never anything for himself.”

When he was sentenced to death in court, Leela said Appu just smiled, held her fingers through the small slit in the glass separating them, and told her, “don’t worry, there’s still the appeal.” Then, when the appeal failed, he reassured her, “don’t worry, there’s still the clemency.” When the clemency was rejected, he said, “don’t worry, we’ll find a way.” Even after the execution notice arrived this week, Appu says to her, “there’s still time, we’ll try”.

Appu’s mother, who lives in a nursing home, has no idea that her son is on death row, let alone that he is scheduled to be executed next week. “Every time I visit her, she asks me when he’s getting out. I keep telling her the case is dragging on, and his hearings have been postponed. She is hopeful that one day, her son will come and bring her home, that she can live out her last years with him.”

A case riddled with problems, a nine-year struggle to save Appu’s life

Leela now lives in a public rental flat with her five children and two grandchildren. Other than caring for her grandchildren, her main focus these past 9 years has been finding a way to save her dear brother’s life. Despite their humble background, Tangaraju’s family and friends have spent $52,000 over the last 9 years just in legal fees. For many years now, Leela has fasted on Thursdays for her brother. She’s visited temple after temple with offerings and vows, she’s sought out astrologers, beseeching them to help her find some way to alleviate her brother’s suffering.

“If I could give my life in exchange for his, I would,” Leela says, breaking down. “Some people have fixed the date and time of my brother’s death and informed me…how will I live with this?”

When he was released in 2013, after his longest stint in prison till then (8 years, of which he served 5 years and 3 months after remission) Leela had hoped Appu would finally have the chance to build a life. His uncle helped him with some start-up funds for a small provision shop, which Leela and he ran together. He was a trooper, and worked hard to take care of the shop, but he struggled to catch with the world, learn the ropes.

He was stressed by the responsibilities he had to juggle, and found the weekly urine tests he had to report to a heavy burden on top of what was already on his plate. It would take up a whole day, with the travelling and queuing up at the centre. He missed a test, and was arrested in January 2014. Even then, Leela wasn’t worried. She thought he’d be out after a short period. He was initially released on bail, but at a further court mention, bail was revoked and Appu was placed in remand.

Months after his arrest, Appu was investigated in relation to the events surrounding the cannabis that another man, Mogan, had been found with in September 2013. The police interrogated him without the presence of a lawyer or a Tamil interpreter. During his trial, Appu testified that he had repeatedly requested for the assistance of an interpreter during the recording of his first statement, and this request was denied. He said he did not fully understand the Inspector’s questions, nor parts of the recorded statement when it was read back to him.

In his judgment, High Court Judge Hoo Sheau Peng explained that he did not put any weight in this because, “…I found rather disingenuous given the accused’s admission that he had made no such request for any of the other statements subsequently recorded from him.” When I read the judgment, I found the judge’s reasoning utterly baffling.

I have been investigated by the police before, on multiple occasions, for my political activism. English is my first language, I’m university-educated, I have friends who are lawyers, and a decent understanding of my rights under the law, and yet, I have found police interrogations intimidating, daunting and exhausting. In every instance in which I have been interrogated by the police, the statement they read back to me sounded nothing like me, because they have no obligation to record statements verbatim. Statements taken by the police are also often riddled with grammatical and other errors.

It boggles my mind that even journalists are obliged to quote interviewees word-for-word, but not the police. Police officers have repeatedly twisted and embellished my words in their statements. Sometimes, I’ve asked them to amend it and been met with resistance. Once, a police officer scolded me for my request to make amendments, saying that it’s very inconvenient for her because then she and I would have to sign against each change, or re-print the statement, if there were too many changes. She even tried to persuade me that a response she had written down was what I had said, though I was certain I would have never said that.

At other times, I’ve just not had the energy to advocate for myself and get the statement changed. After 4 hours of questioning, you just want it to end. So I’ll admit, I’ve signed off on statements just to get out of there.

It is difficult to overstate the power differential between an investigating officer and a man in Appu’s position. Appu was being investigated for a capital charge, he was imprisoned at the time of his investigation, he hasn’t had meaningful access to education, and isn’t proficient in English, the language the officers were speaking to him in.

What’s more, Appu had been conditioned, for around three decades of his life, to submit to police and prison authority. When he made repeated requests for a Tamil interpreter during his first statement-taking and was denied, it makes perfect sense that he would give up and be resigned to going through the rest of his interrogations without an interpreter.

If anyone were to put themselves in Appu’s shoes for a second, I don’t think it is difficult to understand that he would’ve stopped asking for an interpreter, not because he didn’t need one, but because he had given up on the idea that his needs would be met.

Leela’s greatest regret is that Appu didn’t take the plea bargain that the prosecution offered him, before the case went to trial. According to his family, Appu was first offered 20 years, then 15 years, and finally, 12 years. He turned down all these offers because he believed he could prove his innocence in court.

Appu didn’t see or touch the cannabis. He didn’t pay or receive any money for it. There was no evidence that he placed an order for it. So I can understand why Appu was sure he would be acquitted. Appu didn’t believe that, just because there were some calls between Mogan, Suresh and some phone numbers the prosecution said belonged to him, he could be convicted of trafficking and sentenced to death. The mobile phones tied to the numbers were never even recovered for analysis. Appu maintained that one of the numbers was not his, and the other, he had lost. Despite all this, on very thin, circumstantial evidence, Appu was found guilty and given the mandatory death penalty.

Mogan, who is the man who was caught with the 1017.9g of cannabis, was only charged with trafficking 499.99g of cannabis and received 23 years in jail and 15 strokes of the cane. Appu, on the other hand, was charged with conspiring to traffic the full amount of 1017.9 grams, despite there being no evidence that he knew the quantity of drugs that were being transported.

Mogan’s girlfriend, who was with Mogan in the car with the drugs, was given a discharge not amounting to acquittal.

Suresh and Shashi, two others involved in the incident, were charged with conspiracy with unknown persons to traffic in cannabis, were also given discharges not amounting to acquittal. This means all three of them walked free.

From the position of any ordinary person, and especially for Appu’s family, it is so difficult to understand or accept these decisions, and their consequences. It feels shockingly arbitrary and unjust. If Appu had taken the plea bargain, he would have been a free man in three years. But because he decided to fight the charges against him, he faces the noose next week.

“My brother deserves to have his case reviewed fully by the supreme court – they have to relook at his conviction. He didn’t get justice,” Leela beseeches.

Singapore’s drug policy does need to be “thrown out the window”

20th April, a day after Appu received his execution notice, is celebrated as ‘420 Day’, or cannabis celebration day, in many parts of the world. There are parties, gatherings in numerous cities, celebrating the decriminalisation of cannabis, which has freed hundreds of thousands of people from prison, given them their lives back. The international community is increasingly responding to the science around cannabis and embracing its many uses – medicinal or recreational.

Many countries are also reckoning with the grave injustices and harm caused by prohibitionist approaches to cannabis, and moving towards legalisation and regulation. When I was in Vienna last month, at the United Nations’ Commission on Narcotic Drugs, I watched with admiration as some governments acknowledged how the criminalisation of cannabis and other forms of drug use has ruined millions of lives and led to incredible, unnecessary suffering, especially among racially and socioeconomically marginalised communities.

These leaders not only committed to drug policy reforms that centre human rights, harm reduction and health moving forward, they even spoke of how they had a duty to commit to reparations and restorative justice for the many decades of punitive drug policy that have victimised and marginalised drug users.

Singapore’s destructive drug policy has claimed too many lives. The PAP government remains unmoved by science, evidence, international law, diplomatic pressure, or the heart-wrenching pleas of families who are forced to collect cold, dead bodies from Changi prison. The only way to put a stop to their killing spree is for the people of Singapore to rise up, and refuse to tolerate this senseless violence.

In an interview last year, when asked a question about how Singapore’s drug laws aren’t deterring drug kingpins from bringing drugs into the country, and just targeting low-level drug mules, Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said, “If I say I don't catch traffickers and I wait for the kingpins, basically my drug policy will be out of the window.” To that, I say, yes, throw it out of the fucking window.

Spare Tangaraju’s Life - Stop The Execution

The most urgent fight before us is the one to save Tangaraju’s life. His family have called upon the public to protest his execution, and urge President Halimah Yacob to grant him clemency. As Ramadan (the Muslim fasting month) comes to an end and Muslim families in Singapore and around the world celebrate Hari Raya/Eid, let us not allow the sacrifice of yet another brother in our name.

Join us at 2pm this Sunday, as we gather at Istana Park to call on the government to stop Tangaraju’s execution. Tangaraju's family and friends will be addressing the public and the press about the problems in his case, and their struggle for justice.

Family members of other death row prisoners, past and present, will be there in support of Tangaraju's family, and will speak as well. After this, there will be some time for members of the public to write their own clemency appeals to the president, asking her to spare Tangaraju's life. Stationery and sample letters will be provided. At around 4pm, these letters will be delivered to the Istana. RSVP here.

Stand with Tangaraju’s family, demand clemency for him, and insist that Parliament must declare an immediate moratorium on executions in Singapore, so that no other family has to face the terror of a death notice that informs them of when and how the state plans to murder their loved ones. #StopTheKilling #AbolishTheDeathPenalty #SaveTangaraju