I Defy: Why I am not complying with my POFMA Correction Direction

I said what I said.

I defy the POFMA Correction Direction that Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam instructed me to publish on 5 October, via the POFMA Office, because it is unlawful and beyond his powers. I stand by everything I said in my post about Azwan bin Bohari’s execution, which I wrote for the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), and republished on my own Facebook page. There are no false facts in the post. There are only my opinions on the legal process which sent Azwan to the gallows, which happen to be contrary to the opinions held by Shanmugam. Policing my opinions is beyond the scope of POFMA, and an overreach by the Minister.

It is a gross abuse of power to force those with an opposing view to discredit and humiliate ourselves, to publicly “confess” to spreading falsehoods when we have done no such thing.

The Minister is deeply mistaken if he thinks that I will be a mouthpiece for his opinions about prisoners on death row and his attempts to defend the barbaric death penalty regime in Singapore. We should be very wary of politicians who are so insecure about their laws and policies that they cannot tolerate opinions that are in disagreement with their own.

Shanmugam said in Parliament in 2019, when POFMA was first introduced, that it was meant to allow us to have “honest debates” based on a “foundation of truth” — but from his persistent attacks against anti-death penalty activists, it is clear to me that there are few things the Minister fears more than honest debate on this topic or any other issue he feels strongly about.

If Shanmugam is displeased by my opinions, I would gladly engage in an open, “honest debate” with him about whether Singapore’s death penalty regime is just, and we can let the public decide whose arguments are more persuasive. But he won’t do it.

Instead, he aggressively asserts his views on the death penalty in mainstream media, in alternative media, in Parliament, on his social media platforms, in schools, at youth forums, at civil service events, in public addresses — while various authorities make sure death penalty abolitionists don’t have access to any of these platforms.

It is unthinkable, in Singapore, for an anti-death penalty activist to be quoted in a mainstream media article or be allowed to give a school talk. I have been told by multiple journalists that the death penalty is “so far beyond the OB marker” that TJC’s press releases and campaigns, even when clearly newsworthy, are “automatically ignored” by the newsroom. It is incredibly difficult for TJC to find venues in Singapore to hold our events, even when we are prepared to pay market prices for the venue rental. Why? Because most venues are afraid of facing sanctions from the government if they allow us to hold an anti-death penalty event in their space.

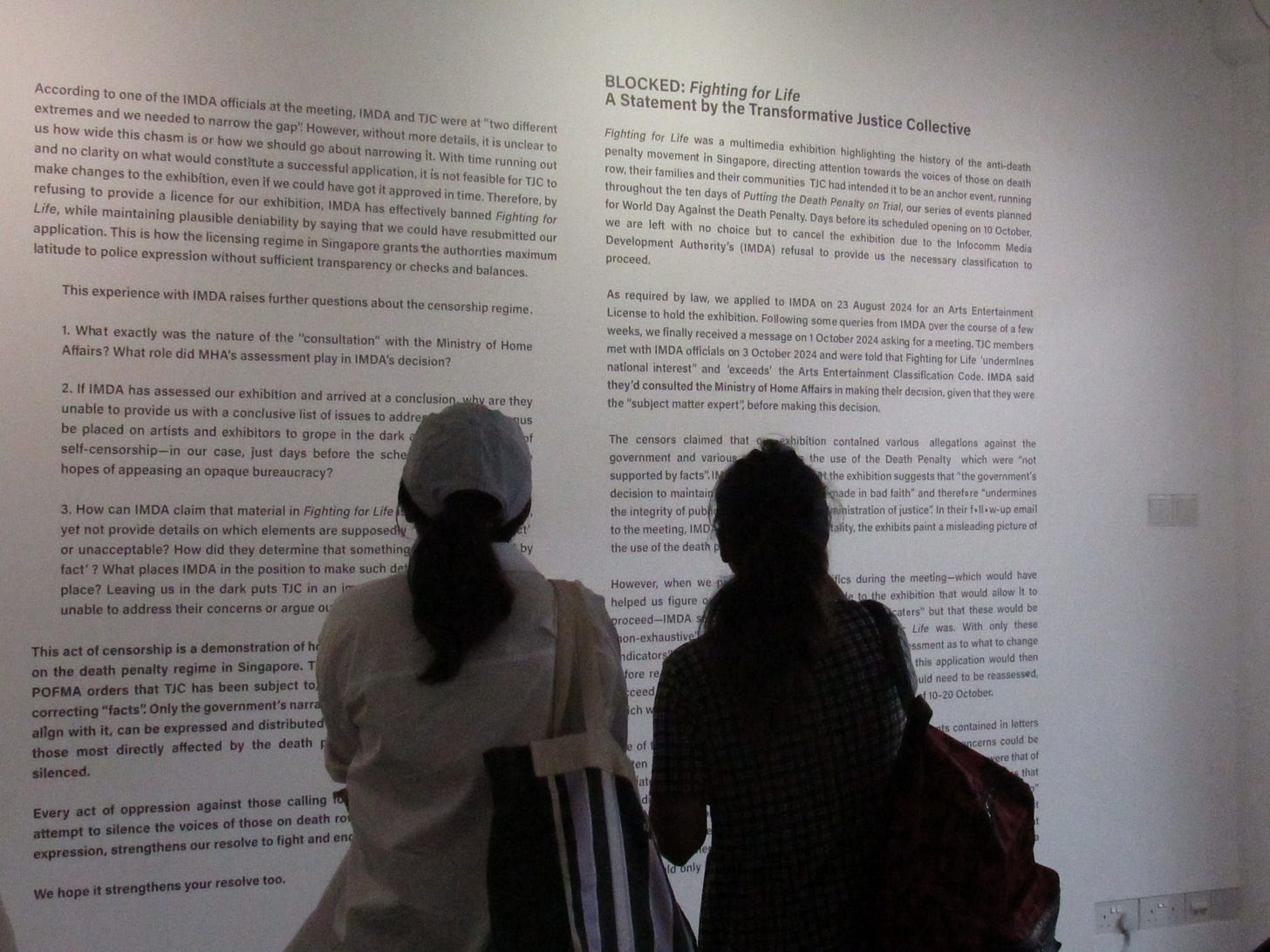

An exhibition TJC put together on the anti-death penalty movement in Singapore, which was supposed to run from 10-20 October at UltraSuperNew gallery, was refused licensing after IMDA (the Infocomm Media Development Authority) consulted with the Ministry of Home Affairs, Shanmugam’s ministry. The exhibition materials we submitted drew attention to the history of Singapore’s death penalty regime, and voices of prisoners on death row and their families. Why aren’t the public allowed to hear these stories, weigh them against the government’s statements, and come to their own conclusions? Are such acts of censorship about safeguarding the truth, or controlling the narrative? When Shanmugam and the rest of the government have so much reach, resources and control over such a wide range of platforms, I find it abhorrent that he still threatens the one space anti-death penalty activists have to share our views — our social media pages.

Well, I’m sorry, the Minister can’t have his say on my Facebook page too. It is a sacred space to me, the space I learnt to find my voice. After I refused to comply with the POFMA order, the Minister instructed the POFMA Office to send a legal demand to Meta and X, directing them to publish a Correction Notice in relation to my posts. MHA has also instructed the POFMA Office to investigate me. None of this will silence me, nor will it stop the anti-death penalty movement in Singapore, which has been growing from strength to strength. We grew up with bullies in power, we know how to fight them.

TJC’s and my commitment to the truth is steadfast. We are fastidious in our fact-checking, disciplined in triangulating data, and principled in our reporting. If we make honest errors from time to time, we hold ourselves accountable to correcting them, apologising to readers, and being transparent about our mistakes. I suspect that it is not any falsehoods, but rather, our commitment to honesty that the Minister finds threatening — because this commitment also means that we don’t mince our words. Our opinions are strong, our criticism of the death penalty regime is scathing, and our commentary is impassioned.

Shanmugam may have the power to issue POFMA orders, and for refusing, the authorities can haul me to court, seek my imprisonment, and impose staggering fines on me. But I have the strength of my conviction, a clear conscience, the kinship of comrades, and the comfort of a community built on real love for the people, for justice, and truth. The likes of Shanmugam may live in mansions, but they can only dream of such riches.

I feel particularly strongly about defying this POFMA order because the way POFMA is used has gotten increasingly ludicrous over time. Some people in power have shifted from using POFMA to slam inaccuracies in statistics to blatantly shutting down critical views and inconvenient truths. POFMA is weaponised as a form of psychological violence against the public when those in power dress up their self-serving opinions as the “correct facts” and shove them down our throats.

I have seen firsthand the stress, shame and trauma that POFMA orders have brought to ordinary people and their families, and I have had enough. I know concerned citizens who were enthusiastic about educating fellow citizens about their pet topics who have retreated after being POFMA-ed, deciding that it is better to “leave politics to the politicians” because of these kinds of attacks. When those who care about improving our society stop speaking up on issues that affect all of us — like housing, cost of living, democracy, etc — it is us, the people, who lose out.

I defy my POFMA order in solidarity with every earnest critic whose valuable opinions, and sincere — even if imperfect — attempts at contributing to public discourse have been attacked thus far.

It is outrageous enough that POFMA is misused to silence criticism, but the “Correction Directions” that TJC and I received go even further, requiring us to parrot Shanmugam’s beliefs about death row prisoners. It should make our blood boil that our politicians think they have a right not just to silence us, but to force their words into our mouths.

I find it particularly important to defy this order because in a recent CNA article on public perceptions of POFMA over the last five years, the Ministry of Law (also Shanmugam’s ministry) is quoted as saying, “The fact that POFMA orders are generally not challenged makes it clear that people who have been issued with the orders knew that they were putting out falsehoods in the first place.” This is laughable. Firstly, even in POFMA cases where there were inaccuracies, they are often honest mistakes, not cases where the person intentionally shared a falsehood.

Secondly, anyone who is paying attention can see that a significant number of people and organisations who comply with POFMA orders go on to put out statements disagreeing with the order and explaining that they complied because the costs of not complying or challenging the order in court are too daunting, and they do not believe they can get justice. It is no secret that Singaporeans are fearful of the government and its attacks on anyone who does not obey them.

And there is a lot to fear when it comes to POFMA. The punishment for not complying with a POFMA order by the deadline given (in my experience, the deadline can be as short as 6 hours after the notice is sent to your email address) is up to $20,000 fine and/or 12 months imprisonment. It doesn’t matter even if you disagree with the order or intend to appeal against it — you still have to comply, or face charges.

I don’t make this choice to defy the POFMA order lightly. I make this choice, even after considering the costs to me and those who care about me, because I feel it is necessary. It’s time to push back against the slew of increasingly repressive laws and practices that have been introduced in recent years which continue to erode what little democratic space we have left in Singapore. These intensified attacks on our civil liberties are against the public interest. They are an assault on our political agency, and our very dignity.

It is our right to have access to a diversity of views, to independent reports, and to information from a variety of sources, so we can make up our own minds on any topic. Literacy isn’t just about learning how to read and write, but learning to discern truth from myth, facts from opinions, and critically engage with different perspectives. We cannot allow ourselves to become illiterate. As people who share this society, we have every right to interrogate the laws and policies that govern our lives, to question injustice, to challenge and check authority when necessary, and to discuss and debate ideas openly so we can build a better future together.

If there is a need for misinformation to be addressed, independent fact-checking bodies are in the best position to do so, not members of the government who have a vested interest in pushing narratives that support their policies and image. If the government wants to counter any claim they believe to be inaccurate, they can simply use any of the numerous platforms at their disposal to communicate their message wide and clear.

The first time I was called in for a police investigation for my activism, I was afraid. The first time I was arrested and put in lockup, I was afraid. The first time I faced charges, I was afraid. Now, in defying this POFMA order and knowing the consequences I could face, I am, once again, afraid. I find it important to admit this, because I don’t want anyone to think I am fearless. I am just an ordinary person — and a highly anxious one at that — who worries about the stress this will put my ageing single mother through, who frets about how I will pay my bills, who carries trauma from the numerous forms and instances of state persecution I have faced over the years, and who dreads the legal battle that lies ahead of me, given that I am already in the midst of fighting the charge brought against me for the letter-delivery to the Istana regarding the genocide in Palestine.

Yes, I am afraid of fines I cannot afford, and prison time. But I am more afraid of what will happen if we don’t stand up for the truth, for our freedom, and for justice, when we are given the chance. I am afraid, over all else, that if I don’t do this, I will lose my moral compass and betray my integrity.

In making this decision, I hold in my heart the death row prisoners who, even from behind bars, fight courageously against a system determined to kill. They have fought for their constitutional rights in court when no lawyer would. Many of them have, on the eve of their execution, told their families, “fight for the others, they still have a chance.” We have a chance, all of us — when the path forks between letting a bully beat us down, and standing up to him. This is what I am choosing to do with my chance.

Here is my response to the specific demands in the Correction Order:

In my post, I drew attention to the fact that the law allows the prosecution to rely on a presumption of trafficking, which, in my view, poses an unfair burden on an accused person—especially one facing the death penalty—to have to rebut. The Minister took issue with this and the Correction Notice required me to say, “In all criminal cases, the Prosecution bears the legal burden of proving the case against an accused person beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Michael Hor, who was a Professor of Law at NUS, writes an opinion very similar to mine in a 2004 article titled ‘The Death Penalty in Singapore and International Law’: “The crux of the matter is the meaning of innocence and guilt…Where the presumption is employed there can be no doubt that it is possible that an accused person can be found guilty and executed in the absence of proof beyond reasonable doubt…” (emphasis mine).

Shanmugam apparently believes that presumption clauses in drug laws do not diminish the burden on the State to prove its case against the accused person beyond a reasonable doubt. I do not believe this. Both of these — Shanmugam’s belief and mine — are opinions. And mine is far from an unusual opinion, let alone a controversial one. It is shared by legal experts around the world, and has been raised many times within and outside of court in Singapore too, especially with regard to capital cases. In fact, there are currently four death row prisoners in Singapore who are challenging the fact that two presumptions were used, in each of their cases, to secure a conviction. Presumptions are controversial in legal jurisprudence precisely because they reduce the burden upon the prosecution to prove each and every element of the offence. It is believed by many reasonable people that presumptions derogate from the right to fair trial and are particularly of concern in capital cases, where the stakes are as high as life and death. Why should there be such a burden upon the accused, when the State has massive resources at its disposal?

The Correction Notice I received also accuses me of claiming that the State arbitrarily schedules and stays executions without regard for due legal process. This is patently untrue. What I said was that Azwan’s execution was first scheduled in April and stayed the night before the scheduled execution, and that his family was told that it was because he had ongoing legal proceedings. This led to their alarm and confusion about why it was scheduled again in October even though he still had a different legal matter before the court. What my comments focused on is the human impact of the death penalty regime and the emotional roller-coaster families go through because they have limited information and understanding of why some decisions are made. The implication of my comments are not that such decisions are made arbitrarily or without regard for due process, but that the legal decisions about when to stay an execution and when to proceed — and the bureaucratic processes involved — are confusing and opaque to loved ones, adding to their pain. And this, I resolutely stand by.

What I found most despicable about the Correction Notice I was ordered to put up was that it required me to say, “Some PACPs abuse the court process by filing last-minute applications to stymie their scheduled execution.” (PACPs refers to Prisoners Awaiting Capital Punishment, a term the government uses to describe death row prisoners). There is no punishment harsh enough to coerce me to repeat this view as the “Truth”. It is, to me, a highly repugnant position.

Death row prisoners are amongst the most vulnerable, powerless and voiceless people in our society, stripped of many rights the rest of us enjoy. The courts, on the other hand, are one of the most powerful institutions in the country. It is very bizarre to me that when prisoners facing an execution try every legal means available to them to air what they believe to be important issues before the court, this is called an ‘abuse’. They and their families are doing everything they possibly can, within the extremely narrow limits of the law, to try and save a life. If any person, especially an unrepresented prisoner, brings a case before the court, I believe it is the court’s duty to give it a full hearing. If they find it to be lacking in merit, then they can dismiss the case.

Just because a Singapore court has pronounced a case to be an “abuse of process” doesn’t mean it is the Truth, or that I have to agree with this characterisation. It is merely the opinion of one, or a few, judges. I can, and do, disagree with them. Judges and courts around the world make mistakes, change their opinions or evaluation of a case over time. Moreover, in any given case, different judges can make different rulings or disagree with each other on the bench too. Appeals, retrials, reviews, etc exist because of the acknowledgement of these possibilities for errors.

Shanmugam might believe that after someone is convicted of a capital offence, and they lose their criminal appeal, they should just accept their fate, and obediently walk to the gallows when their execution date comes, even if they believe that their constitutional rights have been violated, or that there has been a miscarriage of justice in their case. I do not believe this. I believe, as Kalwant Singh - who was executed on 7 July 2022 - said days before his execution, that every prisoner has the right to “fight until the noose is around my neck”. In his name, and the name of every other prisoner executed under this cruel, bloodthirsty regime, I defy this POFMA order.

In the struggle between life and death, those who fight for life will triumph one day.

Solidarity forever.