Death row’s ‘legal scholar’ faces execution this Friday

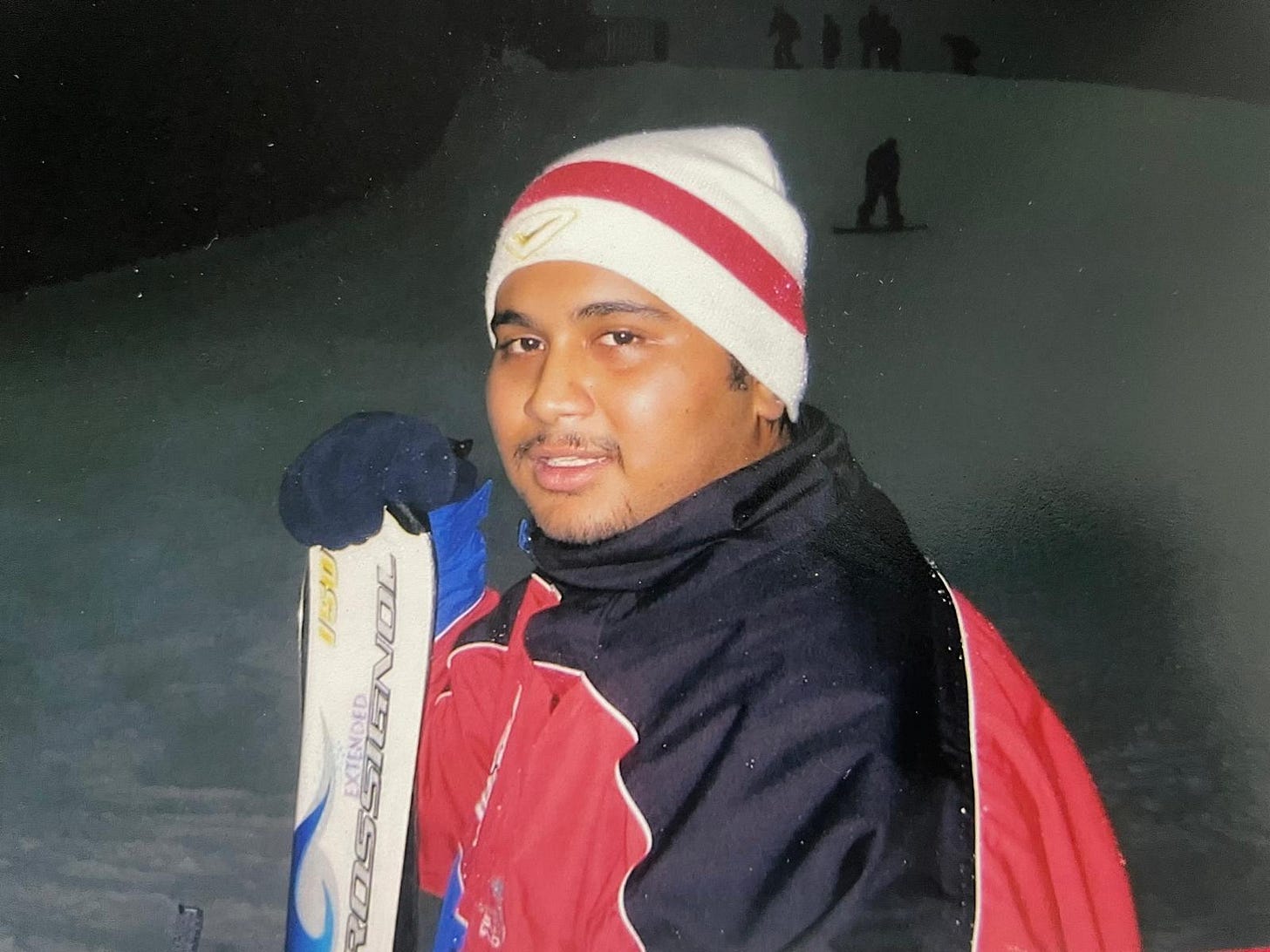

Singaporean Masoud Rahimi was a 20-year-old national serviceman when he was arrested and charged with a capital drug offence. His family is appealing for clemency from President Tharman.

Masoud is representing 36 death row prisoners in a constitutional challenge that has a hearing set for 20 January 2025. He also has an ongoing complaint against his lawyer, which he believes would show how he was prejudiced in the course of his previous review application to set aside his death sentence. But if his execution this Friday goes ahead, he won’t be able to see these efforts through.

“If I go back home, I make sure everybody goes back home. I don’t want to get out of here by myself.”

This is what Masoud tells his half-sister, Maya (not her real name) whenever she’s exasperated with him for focusing on other death row prisoners’ cases when his own situation is so dire.

“He believes God put him in prison to help the others on death row,” Maya tells me.

From teenager to death row prisoner

Masoud was born in Singapore to a Singaporean mother and an Iranian father. His parents separated when he was a child, and Masoud’s father took him and his siblings with him to Iran to raise them there after Masoud finished primary school. A few years later, the family moved to Dubai, where Masoud went to high school.

At 17 years of age, Masoud had to return to Singapore to serve National Service (NS) because of the country’s strict laws around male citizens’ NS obligations. His father tried to appeal to MINDEF to let him finish University first. He expressed concern that Masoud was too young to leave home and cope with life here. Masoud’s father recollects that the MINDEF officer said Singapore is safe, there is nothing to worry about, and denied his request for deferment.

Away from the family he had grown up with, the teenager lived alone in an apartment his father still owned in Bishan.

“He found it very difficult to adjust to life in National Service,” Maya says.

I can imagine what a shock to his system it must have been for a young boy who had already been uprooted multiple times during crucial growing years, to suddenly be thrust into the highly regimented environment of NS, without any preparation or peers to make sense of the experience with.

Maya, who is a few years older, has a different father. She grew up in Singapore, and hadn’t gotten the chance to build a relationship with her half-brother. “He was not back in Singapore for long before he was arrested,” she says.

Masoud was almost done with his NS, and preparing to return to Dubai at the time. He had been discussing many plans with his younger sister, Mahnaz, for their future together as a family in Dubai, and was excited to return to a loving home.

20-year-old Masoud was still a minor under Singapore law when he was arrested in 2010, barely past his teenage years. He is one of the youngest people to face a capital charge in Singapore’s history.

In Masoud’s first statement to the police, he stated that he had been suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as well as an Anxiety Disorder stemming from his time as a national serviceman. Despite making this statement early on, it was not included in the original court documents and was only mentioned on appeal.

“What I remember about him from then…he always dressed like Hip Hop, and he loved to rap!” Maya recollects.

She pauses wistfully, before continuing, “I wish he had never come back to Singapore…he had a stable life, and a good future in Iran. He had never been in any trouble.”

It’s a stormy Thursday evening, and we’re sitting on Maya’s couch in her public rental flat, her daughter and nieces playing in the next room. Neither of us knew then that the next morning, 22 November 2024, prison officers would come to her house to inform her that her brother would be executed in a week.

Maya has been visiting Masoud since 2017, when their ailing mother became too unwell to make the visits. That’s when Maya and Masoud started to get closer. Maya learnt that Masoud was keen to pursue some issues in his criminal case, but didn’t have the help he needed on the outside to take things forward. So she stepped up, and decided to do whatever she could.

“Once Rosman got a notice, Masoud told me his turn may be coming soon. But it doesn’t feel real. He’s been in prison for over 14 years now. The longer he’s there, the more we believe that he will come out one day, that he won’t be executed,” she told me, less than 12 hours before she was delivered his execution notice.

Masoud, the legal scholar

“Masoud is always giving me the names of the other guys, and their family’s contact, asking me to help them. Recently, he asked me to order 27 CDs for Rosman…songs he wanted to listen to during his last week. All the old R&B kind of CDs, you know? Before that, I ordered 24 CDs for one of the other guys! Sometimes, I get impatient and ask him why I should help all the others too. I already have so much on my shoulders with Masoud’s case, my kids, and looking after my ageing mother. Then he will ask me, ‘It’s good to be kind, isn’t it?’ So, I do what I can.”

“Many of the prisoners look to Masoud for help,” Maya explains. Masoud has a diploma, which is a big deal on death row, where most have very little education. Some of the prisoners can’t read or write, and some are elderly. Masoud spends a lot of his time helping them with their legal cases, even drafting formal applications for them like a lawyer would. He admitted to Maya that he often doesn’t even have time to work on his own case.

The generosity of Masoud’s spirit shone through when in July 2022, Masoud gave an argument he had been working hard on for his own case to Nazeri bin Lajim, when the latter received an execution notice. He helped Nazeri draft an application for a stay of execution using this argument, knowing this meant he would no longer be able to use it himself.

“He feels this is his purpose,” she says, and it is clear that she is both in awe of him, and worried for him.

Masoud has taught himself many aspects of the law while in prison. In fact, one of his frequent gripes is that death row prisoners are prohibited access to many law books, such as ‘Modern Advocacy’, a book on trial advocacy in Singapore. I have seen some of the many legal arguments Masoud has composed for other prisoners and himself over the years. They are incisive, innovative and brilliantly written — it is no exaggeration to say that Masoud’s legal prowess would put many lawyers to shame. It is a remarkable feat for a prisoner without any legal training to produce such impressive legal analysis, and it is a powerful testimony to his dedication to helping vulnerable death row prisoners.

From September 2023 to May 2024, Masoud led a constitutional challenge by 36 death row prisoners against the Post-Appeal in Capital Cases (PACC) Act which Parliament passed in 2022. The Act introduces further restrictions for death row prisoners to bring further applications after their criminal trial and appeal had concluded, and the prisoners believe it is a serious violation of their right to access justice. Masoud argued the case on behalf of all the prisoners, against highly-educated and powerful state lawyers. Their case was dismissed on the basis that the law had not come into force yet, and therefore could not be challenged.

In June 2024, the PACC Act came into force. Masoud and the other prisoners decided to mount a fresh challenge in September, once again led by Masoud. The hearing is scheduled for 20 January 2025. If Masoud is executed on Friday, he won’t be able to see this case through, and the other prisoners will have to handle the constitutional challenge on their own.

Even after receiving his own execution notice this week, we heard news that Masoud is continuing to work hard on preparing legal applications for the other prisoners.

Masoud, the sage

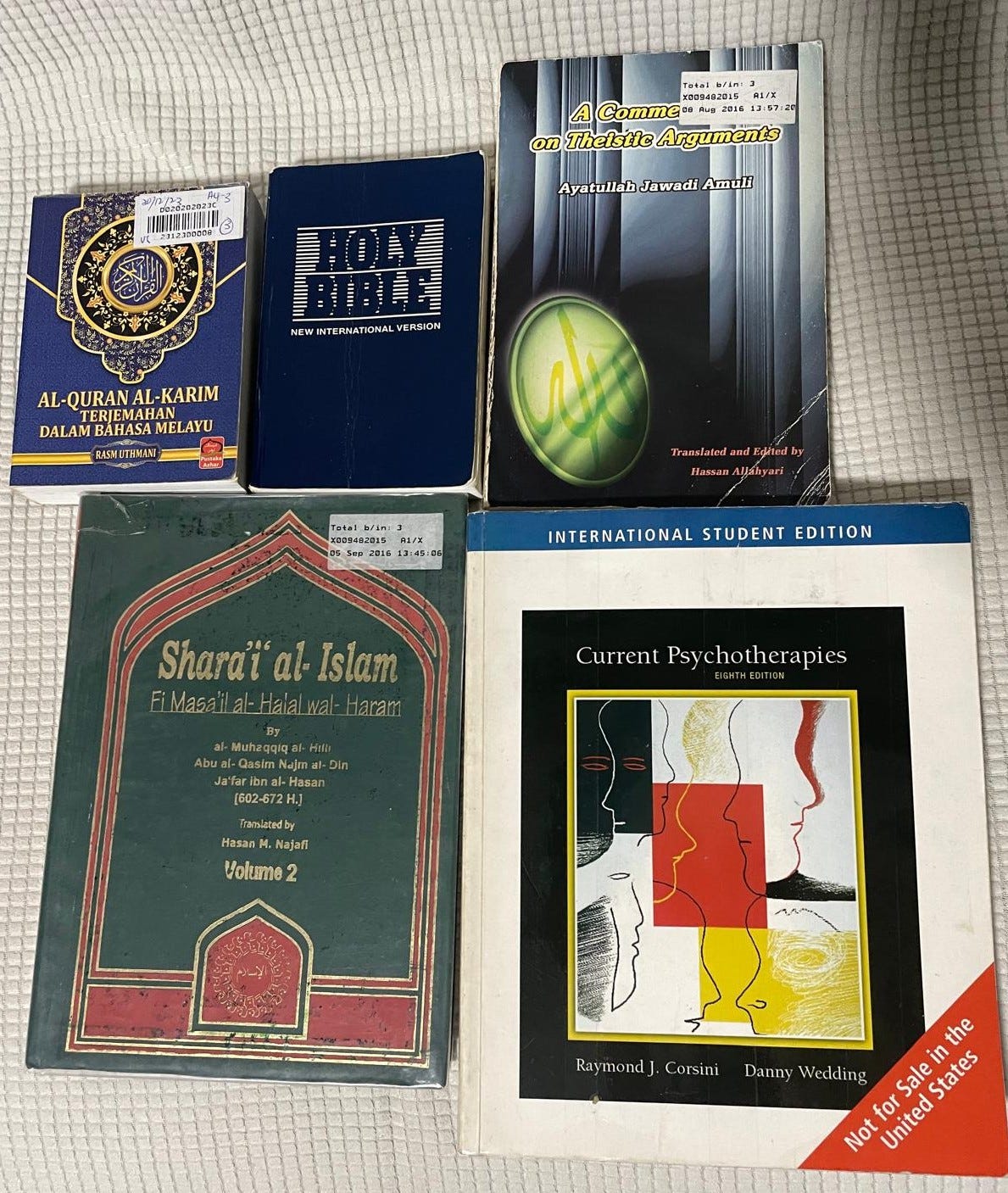

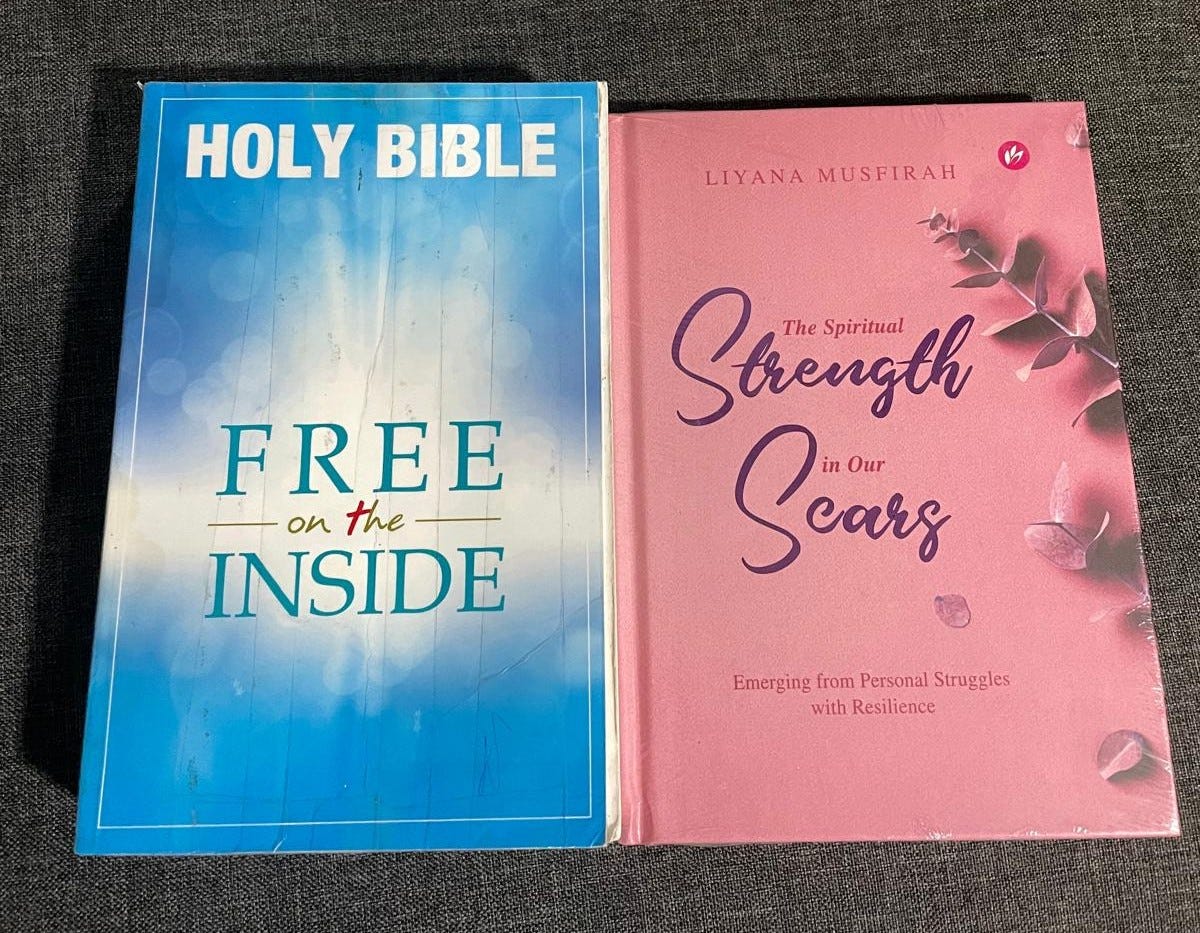

Maya shares how, in the years Masoud has been incarcerated, he has committed deeply to a spiritual path. Many of his letters, whether to family or friends, are peppered with gratitude to God, wishes for his loved ones to experience God’s compassion, and elaborate quotes from the Quran and other texts.

“It’s very peaceful to be with him,” she smiles. “Any problems you have, if you talk to him, he will make you feel better. He is very humble, very positive. The way he looks at things, it’s so different. Not like an ordinary person.”

At one point, when Masoud noticed that Maya was going through a lot, he arranged for her to see a counsellor through his own prison counsellor. Maya was initially reluctant, but Masoud gently persuaded her to try opening up, so she did.

Masoud, the lover of books

When Maya brings up how much Masoud loves to read, I ask her what kind of books he was fond of. She asks me to wait, then goes into her room and pulls out two huge boxes of books to show me. The boxes easily contained around 100 books. A large portion of them were theological books on Islam, Christianity and Taoism. He also appears to have a fascination for mind maps and psychology.

“His prison cell is like a bookshop! He sent all these books out recently because he says there’s no more space in his cell. My niece and I had to wheel the bags out on a wheelchair, we couldn’t carry them. He has hundreds more books inside,” she grins, and it's clear she finds his love for books endearing.

Maya then pointed to two printers in her living room. “You see this? I bought them because Masoud asked me to print 20 volumes of the Quran from the Holy Quran website. Each volume is 300 pages long! Then I have to get them bound before I pass to him. I’ve only managed to print 12 volumes so far…I have 8 left. When I sent some of the previous volumes to him, one of the prison officers asked him, “you have time to read all this ah, before you go?” Of course, he means whether Masoud can finish reading everything before his execution. Why would you ask that? It’s so mean. Masoud just replied quietly, ‘That’s between God and me, how much he allows me to read.’”

Just hearing this secondhand, the cruelty of the officer’s question stung me. It is just one of many indignities the prisoners have to silently tolerate each day.

I find the idea of Masoud’s prison cell filled from corner to corner with books profoundly beautiful. I have often felt despair at how death row prisoners are confined in solitary cells for years on end, and how desperately lonely that must be. But I hope Masoud’s books have offered him the comfort and companionship that a good friend might.

Masoud, the advocate

Masoud has been very vocal about the rights of prisoners on death row, despite the risks he faces in speaking up. One of the issues he has been passionate about is the government’s blanket ban on legal aid for death row prisoners who want to bring applications at a later stage.

When the prisoners lost the case challenging this ban, he wrote in a letter about the judgement, still upbeat despite his disappointment: “It came on my 15th anniversary, since 20 May 2010. 14 years completed. Now doing my 15th year in prison. Never had I imagined to serve such a long time. I’ve spent more time here than my own teenage life out there. I’m grateful to God for this experience and His guidance. Great has been his favour and grace upon us!”

Masoud has also brought up the issue of how death row prisoners are the only prisoners in Singapore who are denied e-letters to and from family members. He questions why family members are not allowed to bring pen and paper into their visits, leaving them unable to remember many crucial matters their loved ones raise because they can’t write them down. In recent weeks, Masoud has been advocating against the heightened restrictions that Singapore Prison Service suddenly introduced on the prisoners’ communications with family members and fellow prisoners, posing dangerous barriers to their access to justice.

The will to fight, and the grace to accept

“If Masoud was given a chance, he would make use of his life well. This, I know. His is not an average mind. I asked him, if you get the chance to come out, you want to be a lawyer? Or you want to work with TJC?” Maya smiles sadly. “Either way, he would want to keep helping the others on death row.”

In one of his letters, Masoud writes about the efforts of TJC (Transformative Justice Collective),“I wish I can be there to do my part. Perchance, by His Grace, one day…:)”

“Where is the second chance for people like my brother?” Maya asks.

“If you try to solve social problems by killing, you have to keep killing,” she declares.

About the different officials who are involved in carrying out an execution, Maya asks, “Who are these people who take up the job to kill others? Do they publish this kind of job ad, asking if you are ready to kill? How can they bear to take someone’s life? If this is my brother’s punishment, what is the punishment for these killers?”

She collects herself. Masoud has spiritually prepared himself to go, Maya repeats to me multiple times during our conversation. He has told her that she must be prepared too, to accept whatever happens.

Masoud says in one of his letters to a friend, “To strive is my choice. As to the result, I let it go and let God deal with it.”

“Masoud always says we have to try our best. But beyond that, if God wants him back, he is ready to go.” As she says this again and again, I get the sense that this is what she holds on to when the horror of their reality becomes overwhelming.

Maya reminds her mother often, “We need to worry about how Masoud feels, not how we feel. Whatever we feel, it is nothing compared to what he is going through in prison, facing the death penalty.”

Each time I talk to Maya, I am struck by how strong and grounded she is. Her efforts to support Masoud over the years are nothing short of heroic — whether it is hunting down the most obscure books he asks for, doing her own investigative work to locate witnesses he needs for his case, and ensuring that, come what may, she shows up week after week for him at the Prison Visit Centre. She is stoic and understated about both her joy and her pain, but it is clear that she loves her brother fiercely and caring for him has become a big part of her life and identity, the way it has for so many sisters of death row prisoners we have worked with over the years. It is, somehow, always the sisters who are the fiercest defenders of their brothers’ lives.

Though Maya speaks mostly in a wry, matter-of-fact tone, there are moments in every conversation where her eyes welled up with tears that she quickly brushes away and repeats, “He’s prepared. If he has to go, he will go.”

Masoud’s last stretch

Masoud and his family are currently appealing for clemency from President Tharman Shanmugaratnam on the basis of last month’s court ruling that the Singapore Prison Service and Attorney-General’s Chambers committed illegal acts when they forwarded and read Masoud’s private and confidential letters without his consent. These unlawful acts throw into question the credibility and uprightness of the relevant authorities.

Masoud was also a minor at the point of arrest. It is not uncommon for young people to have their charges reduced because of their age and innocence — Masoud’s family and the Transformative Justice Collective urge President Tharman to pardon him on this basis.

Another issue is that Masoud held both Singapore and Iranian citizenship at the point of his arrest, and has not relinquished his Iranian citizenship to this day. Therefore, the Iranian Consulate should have been informed when he was arrested, but this was not done. Consular assistance is mandated under the Vienna Convention for Consular Relations, which Singapore has acceded to, but Masoud was not given the opportunity to receive this assistance after he was detained. This too, adds to the reasons why Masoud should be given clemency.

Further, Masoud has an ongoing complaint against the lawyer who handled his criminal review application in respect of the unlawfully forwarded prison correspondence. He also has an ongoing complaint against his lawyer, which he believes would show how he was prejudiced in the course of his previous review application to set aside his death sentence. But if Masoud is executed this Friday, he will never learn the outcome of this complaint or be able to act on it.

Masoud is also filing an application for a stay of execution on the basis of two new witnesses who have come forward to provide evidence that could demonstrate that he was a mere courier in the case. Both witnesses’ accounts point to the existence of Masoud's boss, Alf, which the court had said "could very well have been a character conjured up by Masoud in aid of his own defence".

Recently, after going to great lengths, Masoud and his family managed to locate one material witness, who is currently incarcerated at Changi Prison. However, as the witness is currently in a punishment cell, he is unable to provide an urgent affidavit. A stay of execution would allow this witness’ testimony to be brought before the court once he is out of the punishment cell.

Masoud has been actively trying to bring these issues before the court for years, but it has been very challenging for him to take the necessary steps because he is on death row with very limited access to the outside world, and without the financial and legal resources he needed to bring this evidence before the court. What’s more, it was only after Masoud was given the execution notice last Friday that Natasha, the second witness, decided to provide her testimony.

The court should allow this new evidence to be presented and properly consider it. We hope that Masoud’s stay of execution is granted so that he is given this crucial and final opportunity to bring this new evidence before the court.

Masoud’s final wish

I ask Maya what Masoud’s final wishes are, if we don’t manage to stop his execution.

“He really hopes to see his Iranian family. Masoud has requested the prison to grant him a two-week execution notice as his family members need time to apply for visas and travel here to visit him.”

However, Maya says the prison refused. The prison used to give non-Singaporean prisoners with overseas families two weeks notice in the past, but for some reason, this hasn’t been granted in more recent cases.

Masoud’s biological father, step-mother and siblings are all overseas, and require visas to enter Singapore. They were only informed on 22 November 2024 about his execution that is scheduled to be carried out on 29 November 2024. They immediately started making arrangements to come to Singapore, but they are worried that they won’t make it time to see Masoud alive.

In case Masoud’s appeals for clemency and the stay of execution fail, his family appeals for at least a longer notice, so that they are allowed to see him for the last time and say goodbye.

Stop the slaughter

Changi Prison’s body count is piling up with back-to-back executions in recent weeks. Precious lives of people — people who yearn to live, to learn, to hold their loved ones, to be given just one chance — are taken in the name of our safety, in the name of supposedly overwhelming public support. The state claims that Singaporeans are as bloodthirsty as they are, but I don’t believe this to be true.

As people of conscience, of compassion, we must rise up and make it clear — no more blood on our hands.

To stop the executions, we urgently need a moratorium on the death penalty. Please sign the people’s petition for moratorium, and do whatever you can to spread attention, and put pressure on President Tharman to grant clemency to Masoud.

Masoud and the others on death row depend on us to act with urgency.