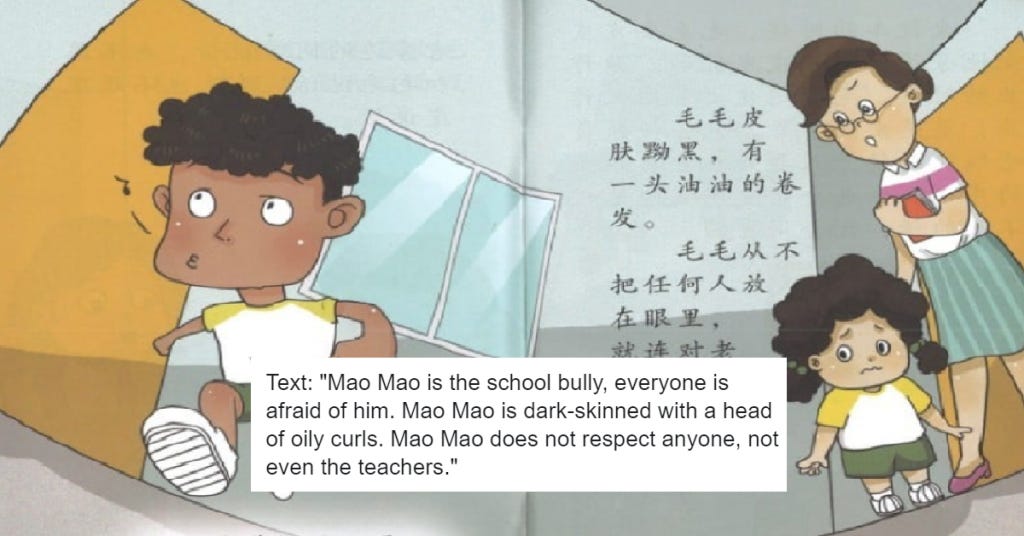

The depictions of Mao Mao, a character in a Chinese-language children’s book called Who Wins? by Wu Xing Ha has come under scrutiny recently. In the book, published by Marshall Cavendish Education, Mao Mao is a dark-skinned, hairy, oily, aggressive school bully who is rude to everyone. Following feedback and complaints from readers, the National Library Board has removed the book for review and Marshall Cavendish has decided to cease the sale and distribution of this series and recalled the books from retail stores.

Mao Mao’s villainy as described in the book evoked for me many conversations I've been having in the course of a research project on ethnic minorities' lived experiences of race and racism in Singapore. These interviews have been illumining and affirming in how over the course of grappling with our experiences together, my respondents and I discover language for our shared histories of displacement within Singapore society. It came as no surprise that almost every Indian respondent I've spoken to - across linguistic, caste and class backgrounds - situates some of their most significant memories of racialised pain in the school environment.

(Photo: Umm Yusof/Facebook)

Anecdotes of classmates using racist slurs, or complaining of oiliness, smelliness, darkness of skin, jeering at the way our tongues or bodies move, not wanting to touch us or share things with us, etc are well-understood and are recounted quite prominently in conversations around race in Singapore. The relentless bullying that many Indian kids experience in school is perhaps why Mao Mao being characterised as a bully is particularly perverse. In addition to these more overt instances of racism, there are many other formative experiences in school that are also racialised, but subtler. I want to discuss two of these phenomena here, which I’ve observed happen repeatedly, across generations.

For one, the early sexualisation of Indian children by their peers (for me, and others I’ve spoken to, it started in Primary 1), in how persistently they are teased about and paired up with another Indian child - assigned a different gender from them - in their classroom. Even as children (or maybe especially as children), we understand that this is not good-natured teasing. It is mockery, in a circus-like fashion, where your bodies and your awkward squirming, your discomfort and embarrassment are the spectacle. It is a very effective form of ‘othering’, where you are both comical in yourselves, but particularly laughable when paired up.

I also noticed, acutely, how this didn’t happen to the other kids. We were the only ones who were teased. I believe that the most profound effect this had was on our feelings towards each other. Even before we had become friends, or gotten to know each other at all, our relationship had projected onto it an intimacy we couldn’t comprehend in our bodies or minds. Then, one of a few things happens, typically. You’re repelled by the other child, whom you see as the cause of your suffering, and you’re determined to distance yourself from them in an effort to escape this. This is the most damaging – when you learn to associate other Indian kids with your shame (this happens in a few other ways too, not just through pairing up). Otherwise, you believe that this child is your girlfriend/boyfriend, because this label has been assigned to you, though you don’t understand what such a relationship means. I wonder what we would find if we studied how experiences like these shape gender relations within Indian communities.

In Primary 5 and 6, I was close to a Chinese boy in my class, and had a deep fondness for him. I remember learning an important lesson about desirability from the fact that despite spending a lot of time with him, and being very open about my liking for him, I was never teased with him. Instead, I continued to be teased with the Indian boy I was paired up with in Primary 1, with whom I had come to share an affectionate, yet unnecessarily fraught and confusing relationship over the years.

I talked to a friend about these experiences some time ago, and within a week after our conversation, she called to tell me that her son, who had just started Primary 1, came home to tell her that the other Indian kid in his class was his girlfriend. When she asked him if it’s because they liked each other a lot, he said no, it’s because their classmates told them so - they called her his girlfriend, so it must be right. She and I were amazed that her son and I had identical experiences, 25 years apart.

The second phenomenon resonates more closely with how Mao Mao is depicted in this book. Indian children’s behaviours are often coded by teachers and school management as deviant. Through my interviews, I’ve come to notice some distinct patterns in how these tropes are produced and reproduced. If we are extroverted, speak up in class, ask questions, show enthusiasm, etc we are often accused of being talkative, disruptive, troublesome, distracted, argumentative (cf: Mao Mao is also described as rude to his teachers).

(Photo: Umm Yusof/Facebook)

One of my happiest memories of primary school is how much my Tamil teachers celebrated me. This was particularly so because every other teacher scolded and punished me at every opportunity. I spent many days sitting outside the classroom or standing at my desk, I was rapped on my knuckles, shouted at in front of the class, even caned on stage. So out of curiosity, when my respondents told me that they got into trouble a lot with their teachers in school, I asked them how their Tamil or Malay teachers felt about them. “They adored me!” the would say, eyes lighting up. Often, these teachers found our precociousness endearing and to be an indicator of competence. They sent us for storytelling, debating and oratorical competitions because we clearly had a lot to say, and showed off about us to Tamil/Malay teachers from other schools.

It is of course a trite stereotype that Indians are talkative/argumentative. Lee Kuan Yew famously claimed that Singapore wouldn’t have worked if Indians were the majority group because we believe in the politics of contention, of opposition. Needless to say, there are many of us who are quieter, introverted, non-confrontational, less verbose, etc. But we also cannot ignore that there are particular cultural sensibilities – at the level of family, community – that we internalise or are socialised to experience as acceptable, even valuable, which we may go on to find are in conflict with mainstream Singaporean Chinese values and sensibilities. The first time minority children encounter these values are usually as behaviours and norms we are expected to conform to in school. At home – like with my Tamil teachers later on – I received a lot of affirmation for speaking up. My mother still tells people with a lot of pride that I started talking when I was 8 months old. Relatives and family friends would joke good-naturedly that I swallowed a mic as a child, because I was so loud. This trait was embraced as part of my development and personality.

In addition to this, I was surrounded by people who expressed themselves uninhibitedly. For better or for worse, crying, shouting, intense conversations, raucous laughter and animated debates were par for the course in our living room. I got into trouble for lots of things at home, but never for talking too much, asking too many questions or expressing my emotions and thoughts vividly. The first time this behaviour was censured was in school. And this in turn affected how these characteristics were perceived at home, when report card after report card complained that I was too talkative, too disruptive, just too much.

This censure has continued throughout my life in Singapore – doctors think I ask too many questions, bosses find me too opinionated and argumentative, I am perpetually described as too intense. The year I spent working in Tamil Nadu, I felt immensely liberated for an unexpected reason – nobody thought I was too much. Heated debates, frank discussions, contesting authority were all regular fare, and I didn’t stand out for these behaviours. Growing up in Singapore, I always saw myself as the problem, and it has been a lifelong endeavour to fix myself in this and other aspects, to become more palatable. But I’ve also learnt that the discomfort my expressiveness brings to the table is heightened because my opinions themselves are often unpopular or marginal, and no matter how gently, how respectfully I express myself, I can’t shake this baggage off. I’ve spent too many hours agonising over why my more outspoken Chinese colleagues (especially if they are anglophone, upper class and from elite institutions), can be frank and direct without being penalised, while I have to carefully curate every critique.

Our outspokenness is not the only thing that is policed, in Singapore. There are numerous other qualities or expressions for which Malays and Indians are labelled as deviant, misaligned, out of step, backward, uncivilised, aggressive, problematic. There are only a few ways to try and escape being continually undermined and punished for being different. One is to adopt and mimic mainstream Singaporean Chinese values and sensibilities as best we can, and distance ourselves from anything and anyone who is unable to approximate it as well as we do. This option is only available to those who can accumulate the requisite cultural and social capital (which is often tied to financial capital). Another is to find sanctuary in kinfolk who embrace us, and for this, we may be accused of being insular. (There are, of course, other strategies people may have, this is non-exhaustive!) But to merely be ourselves is to be disruptive.

When I read about Mao Mao, I thought about Preeti Nair, Subhas Nair, Raeesah Khan and Alfian Sa’at too. About how when we speak, when we challenge, we are seen as dangerous, threatening, offensive. About how every expression of displeasure that isn’t annotated, constrained and sanitised, is fearsome and reprehensible.

Maybe Mao Mao isn’t rude. Maybe his teachers and peers just don’t want to hear what he has to say.

Thank you Kokila for sharing your story. The practice of othering prevails across many ages, environments and circumstances, sad to say. I was told at 17 that a boy I had never even spoken to was my boyfriend because we were similarly plump and bookish. Racism is however something much more insidious than othering based on appearance or habit. It makes one oversensitive, overcautious, just not oneself. Be yourself...it is the best thing you can do. To reject your identity is just too painful a path a consider.

I feel sometimes some people overreacting but maybe due to individual experience. It s a good story and educational! Why not think everyone equally regardless appearance! Read it with relax heart like telling kid Just a story.. and a Chinese saying “do not 对号入座!”